From Ancient Palms to Modern Rackets

Imagine tennis played with bare hands against monastery walls, or on an hourglass-shaped court. The journey of tennis from these early forms to the global sport we know today is a story of continuous innovation and surprising connections to other ball games. Far from being an isolated invention, tennis is a rich tapestry woven with threads from diverse ancient and medieval sports. Its evolution showcases human ingenuity, adaptation, and a constant drive for competitive refinement.

The transformation of tennis from a simple hand-ball game to a sophisticated racket sport mirrors a broader human progression. The initial use of the palm in games like “tjhen” and “jeu de paume” evolved through an iterative design process: from bare hands to gloves, then thong bindings, a paddle (“battoir”), and finally the modern racket. This progression was a continuous search for more effective ways to interact with the ball, aiming for greater power, control, and reduced physical strain.

Royal patronage, notably from Louis X of France and Henry VIII of England, was crucial for the game’s survival and formalization. This support provided resources for dedicated indoor courts and a platform for rule codification, elevating the game beyond a mere pastime and ensuring its legacy.

The Genesis of the Game: From “Jeu de Paume” to “Real Tennis”

Ancient Roots: Hand-Ball Games Across Civilizations

The fundamental concept of striking a ball back and forth, central to tennis, has ancient origins. One of the earliest known precursors was “tjhen,” played by ancient Egyptians, involving hitting a ball with the palm. Greeks and Romans also engaged in various hand-ball games. Some accounts even trace the game’s beginnings to fertility rites, with references by Herodotus as early as 450 B.C.. These ancient games established the core principle of competitive ball-striking, a bedrock for many modern racket sports.

The widespread existence of hand-ball games across diverse ancient civilizations suggests a universal human inclination towards competitive ball-striking. This indicates that tennis is a sophisticated refinement of a very old, widespread human activity, highlighting a convergent evolution in sports where similar solutions arise independently for play and competition.

The Medieval Court: “Jeu de Paume” and its Royal Ascent

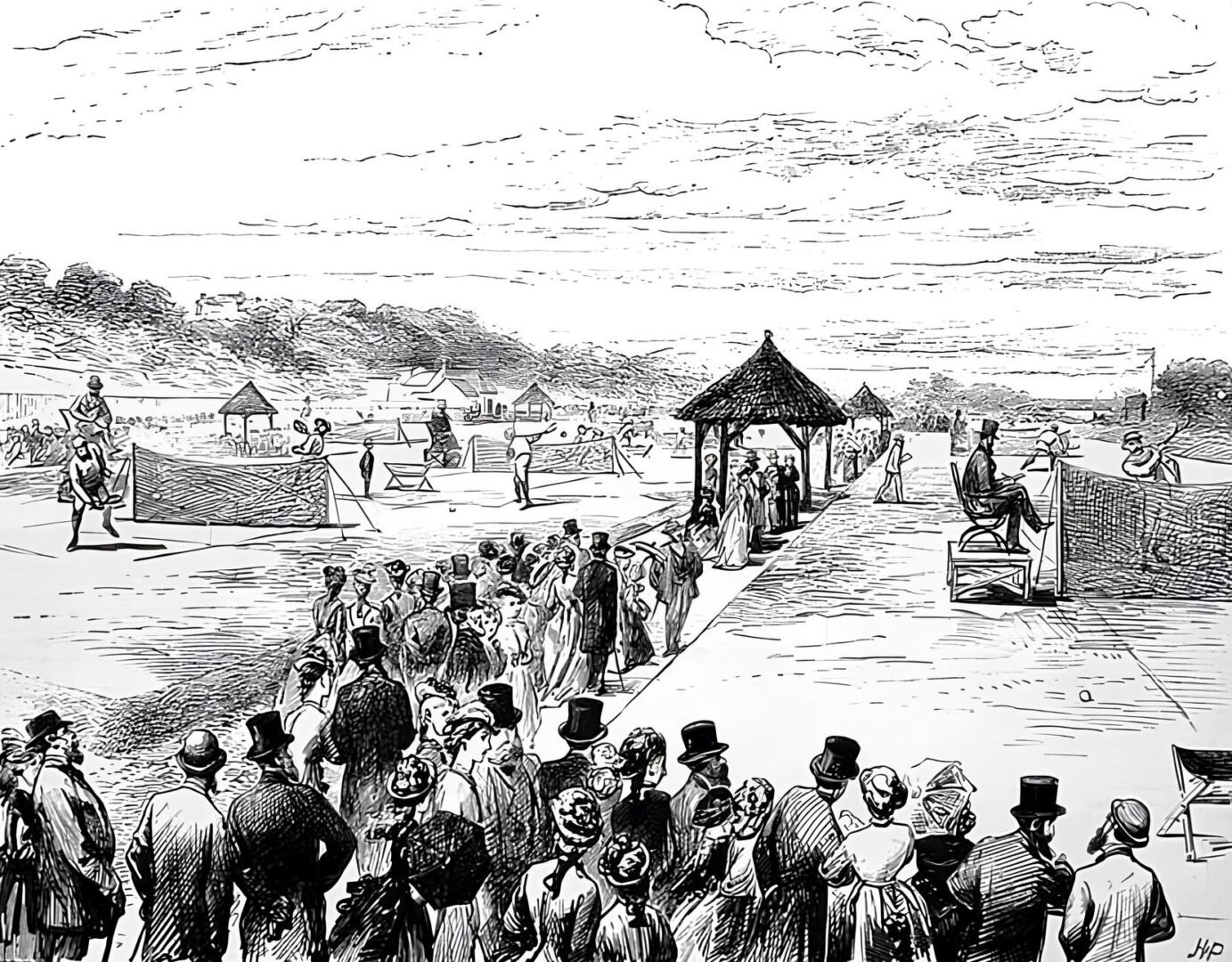

The direct ancestor of modern tennis, “jeu de paume” (meaning “game of the palm”), emerged in 12th-century northern France. Initially, players struck the ball with bare hands. It was often played in monastery courtyards, utilizing walls and sloping roofs as part of the playing area. This adaptation to existing architecture significantly influenced the game’s early design and playstyle.

“Jeu de paume” quickly gained popularity across Europe, becoming a favored pastime for all classes, including royalty. Louis X of France was the first to construct indoor tennis courts in Paris around the late 13th century. England’s Henry VIII was also a prominent enthusiast. The word “tennis” itself is believed to come from the French “tenez,” meaning “hold!”, “receive!”, or “take!” used by the server.

Equipment evolved gradually: from bare hands to gloves, then thong bindings, a paddle (“battoir”), and finally rackets in the 16th century. This technological leap was driven by the need for greater power, control, and reduced hand strain, paving the way for modern tennis tools.

The “Sport of Kings”: Real Tennis and its Complex Legacy

“Real tennis” (also known as “court tennis” or “royal tennis”) is the original racket sport from which modern “lawn tennis” is derived. It was truly the “sport of kings”. This ancient game is played in specially designed enclosed courts with four walls, often incorporating unique architectural elements like the “tambour” (a buttress), “galleries” (openings), and the “dedans” (a long opening at the service end). No two real tennis courts are exactly alike. These unique features are a direct legacy of its indoor origins in monasteries and chateaux.

The rules of real tennis are significantly more intricate than modern tennis, incorporating concepts like “chases” – where the second bounce of the ball is marked, deferring the point – and specific “winning openings”. These complex rules encourage strategic deep shots. The complexity, particularly “chases,” reflects a historical preference for strategic depth, possibly influenced by gambling in early forms of the game.

Real tennis balls are cork-cored, handmade, and heavier (approx. 71 grams) and less bouncy than modern lawn tennis balls (approx. 57 grams). Racquets are short, asymmetrical, wooden, and strung with tight nylon. The lopsided head design helped players hit the low-bouncing balls. While scoring shares similarities (15, 30, 40, deuce, advantage), the winner’s score is called first, and service always originates from the same end. Skilled real tennis players “cut the ball” (undercut it) for sharp drops after hitting the wall, contrasting with modern topspin.

The Birth of Lawn Tennis: A Blend of Innovations

Croquet’s Green Influence: The Outdoor Transition

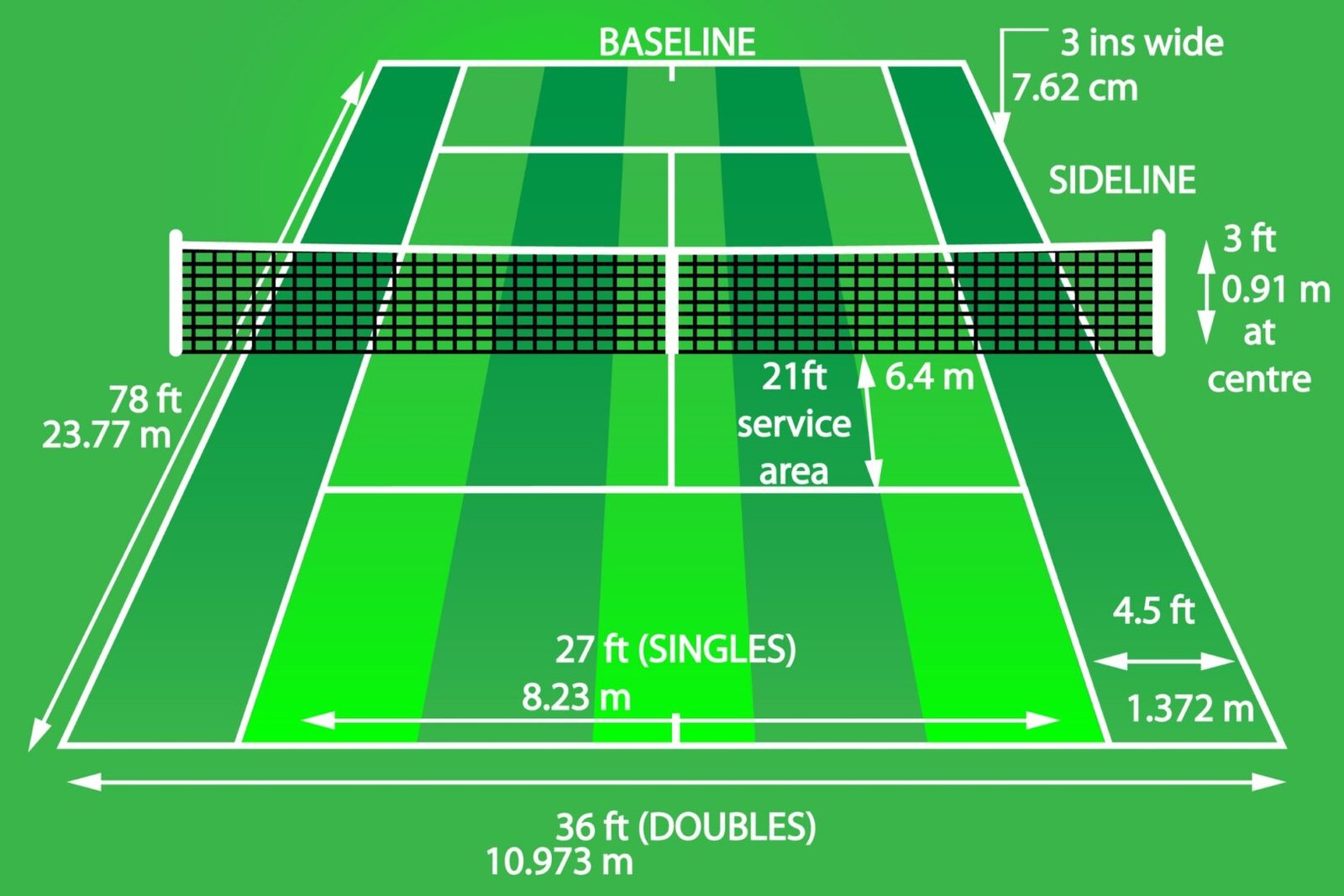

The shift of tennis from indoor courts to outdoor lawns was significantly aided by the invention of the first lawn mower in Britain in 1830, which facilitated the maintenance of grass courts. By the late 19th century, lawn tennis began to surpass croquet in popularity. The All England Croquet Club strategically repurposed existing croquet lawns for tennis. A modern tennis court (78 by 36 feet for doubles ) is approximately half the size of a full-size croquet lawn (32 by 26.6 meters ), suggesting a direct influence on early court dimensions. This “borrowing” of space and existing infrastructure accelerated the rapid adoption and spread of lawn tennis.

Pioneering Visionaries: Gem, Perera, and Wingfield

Key figures in the late 19th century shaped lawn tennis. Between 1859 and 1865, Harry Gem and Augurio Perera developed a game combining elements of racquets and Basque pelota, played on Perera’s croquet lawn. They founded the world’s first tennis club in Leamington Spa in 1872, where “lawn tennis” was first used.

Major Walter Clopton Wingfield, a British army officer, patented “sphairistikè” (Greek for “ball-playing”) in December 1873, which became known as “sticky”. Wingfield is widely credited with popularizing modern tennis through his astute marketing. He produced boxed sets with a net, poles, rackets, balls, and standardized rules. His strategic dissemination, leveraging connections with clergy, law, and aristocracy, led to thousands of sets being distributed globally in 1874. Wingfield’s initial court design was hourglass-shaped, possibly for patent differentiation or influenced by badminton . The world’s oldest annual tennis tournament was held at Leamington Lawn Tennis Club in 1874, predating Wimbledon by three years.

The combination of “racquets and the Basque ball game pelota” by Gem and Perera , alongside Wingfield’s potential influence from badminton , illustrates a pattern of hybridization in sports innovation. New sports often emerge by blending elements from existing games, showcasing continuous cross-pollination of ideas.

Early Rules and Standardization: Shaping the Modern Game

The first Championships at Wimbledon in 1877 were pivotal for rule standardization. The Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC), with the All England Croquet Club, established a new, standardized set of rules for tennis in 1875, which, with minor adjustments, were largely in use by 1880 .

Early rule-makers drew heavily from “real tennis,” adapting its scoring (15, 30, 40, game) and introducing the concept of allowing the server one fault (two chances) . Standardization was crucial for global expansion, making the sport universally playable and comprehensible, a prerequisite for international competition and professional tours.

The International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF), founded in 1913 by twelve national associations, became the officially recognized global authority by 1924 . It promulgated the official ILTF Rules of Tennis . The United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) joined in 1923 after compromises, including abolishing “World Championships” titles and agreeing English as the official language for rules . This reveals early geopolitical dynamics in sports governance.

Since the 1890s, modern tennis rules have been remarkably stable . Notable exceptions include the tiebreak system, designed by Jimmy Van Alen , and the removal of the server’s foot-on-ground requirement in 1961 .

Sporting Synergies: How Other Games Shaped Tennis

Scoring System: A Peculiar Inheritance

Tennis has a unique scoring system: 15, 30, 40, “love” for zero, and “deuce”. This contrasts with most other racket sports like squash, badminton, and table tennis, which use conventional point-by-point scoring. The precise origins remain largely mysterious, with no definitive proof for various theories.

- Court Advancement Theory: One theory suggests it derived from “jeu de paume,” where players advanced on a 90-foot court. Scoring a point meant moving 15 feet forward, then another 15 feet, but the third point only allowed a 10-foot move (to 40 feet) to prevent players from getting too close to the net.

- Clock Face Theory: Another theory posits a clock face was used as a scoreboard, with the hand moving to 15, 30, 45, and a full rotation signifying a game. However, this is largely dismissed as clocks with minute hands were not common when the system originated.

- “Love” for Zero: Theorized to come from the French “l’oeuf” (egg), visually representing zero . Alternatively, it might stem from playing “for love,” meaning for honor rather than money.

- “Deuce”: More clearly traceable to the French “a deux du jeu,” meaning “two points away from game”.

The persistence of tennis’s idiosyncratic scoring, despite its unclear origins, highlights the powerful role of tradition and historical inertia in sports. This adherence to an archaic system, solidified by early governing bodies like the All England Croquet Club at the first Wimbledon , suggests that unique historical quirks can become part of a sport’s identity and appeal.

Court Dimensions: Adapting to New Landscapes

Tennis court dimensions evolved from irregular “jeu de paume” spaces to today’s standardized courts. Early indoor “real tennis” courts were long and narrow (around 90 feet long and 27 feet wide), constrained by existing rooms. No two real tennis courts were exactly alike.

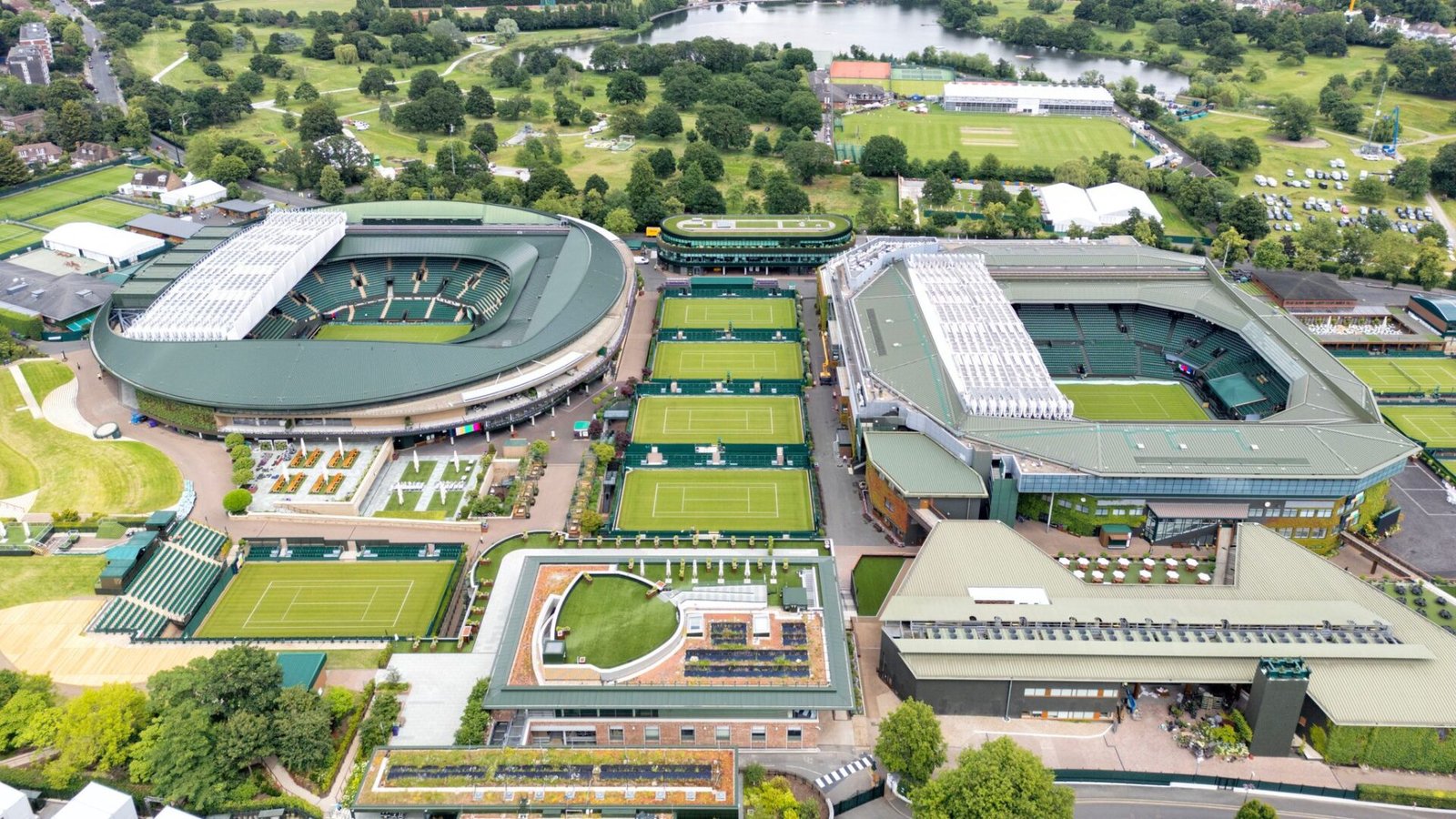

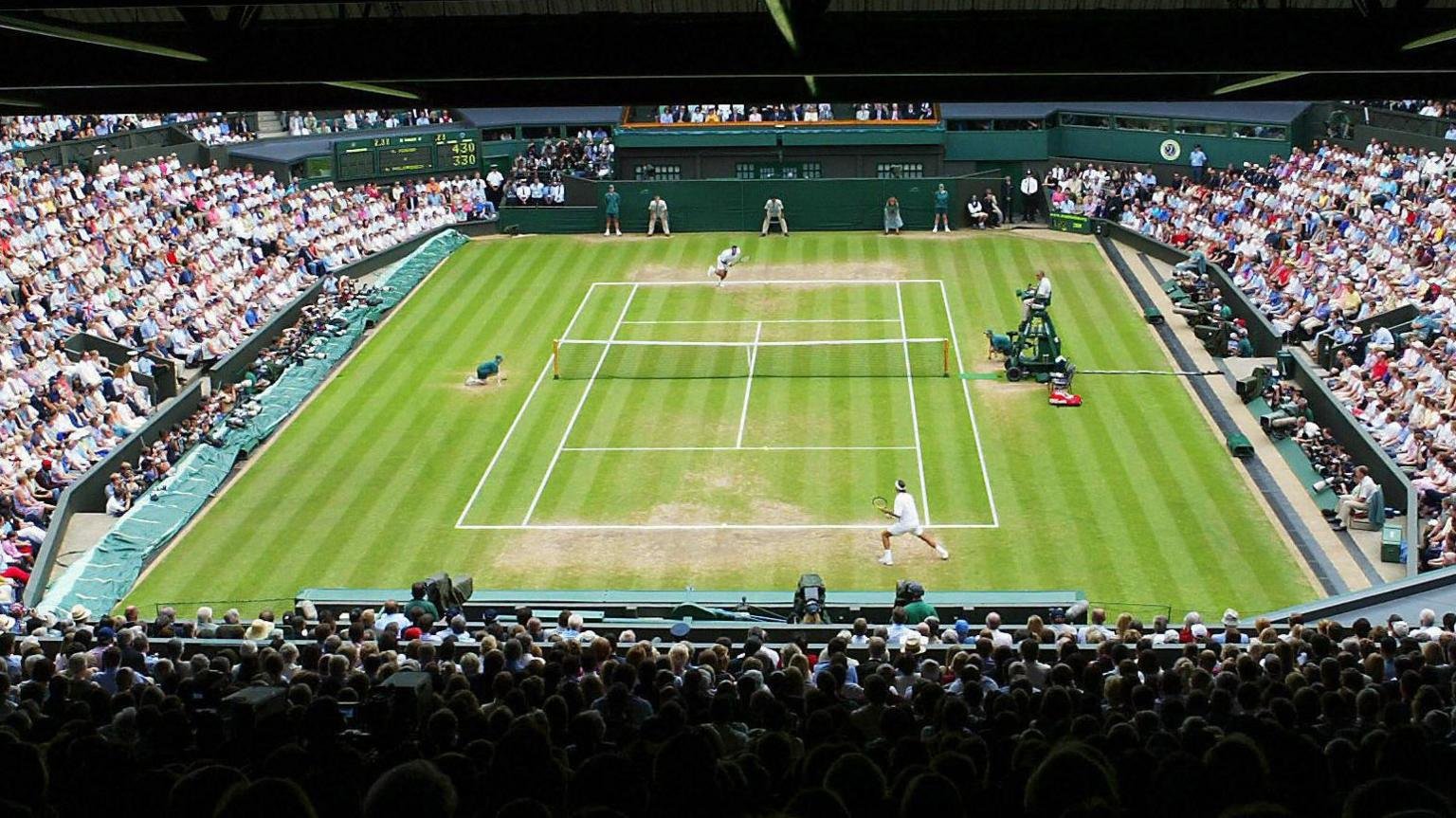

The shift to outdoor lawn tennis in the 19th century led to new court designs. Early courts often fit within existing croquet lawns. Major Walter Clopton Wingfield’s “sphairistikè” initially featured an hourglass shape. However, by 1875, the All England Croquet Club adopted a rectangular design. The first Wimbledon tournament in 1877 solidified these dimensions: 78 feet long, 27 feet wide for singles, and 36 feet wide for doubles .

These dimensions have remained remarkably consistent since 1875 . Today, the International Tennis Federation (ITF) standardizes court dimensions for fairness and consistency across professional tournaments. Net specifications are also standardized: 3.5 feet (1.07 meters) high at the posts and 3 feet (0.91 meters) at the center. This standardization was crucial for global expansion, enabling consistent competition worldwide.

Equipment Evolution: From Wood to High-Tech Composites

The evolution of tennis equipment, especially rackets and balls, has been a continuous process driven by materials science and engineering.

- Early Rackets: From the 16th century, rackets were entirely wooden, often with long handles and small, lopsided heads, borrowed from “real tennis” to hit low-bouncing balls . They were heavy and offered minimal comfort.

- Mid-20th Century Transition: Manufacturers experimented with metals like steel and aluminum for durability and lighter weight . However, early metal frames often damaged natural gut strings and were prone to rusting.

- Graphite Revolution: The 1970s and 1980s saw the introduction of graphite . Graphite rackets offered exceptional strength, stiffness, and lightweight construction, allowing for greater swing speed and power . This enabled oversized heads and underweight frames, expanding the “sweet spot” and making the game more accessible.

- Modern Composites: Today’s rackets use blends of carbon fiber and other composite materials for optimal power, control, and comfort . Innovations like wider body frames and advanced string technology (nylon, polyester) enhance performance, allowing for increased spin, speed, and precision . Players can serve approximately 17.5% faster with modern rackets compared to those from the 1870s.

- Tennis Balls: Initially made of wool, making them heavy with poor bounce . Later, simple rubber spheres, sometimes covered in flannel . The core composition has been refined for consistent bounce, durability, and speed . The yellow tennis ball was introduced in 1972 to improve visibility on television .

Professionalization and Global Expansion

Tennis transformed from an elite pastime into a major professional sport. The professional circuit initially lacked formal competitions. This changed in 1926 when promoter Charles C. Pyle organized a professional tour featuring stars like Suzanne Lenglen. Despite “amateur” players being paid “under the table,” a clear distinction persisted, with “defectors” to the pro ranks banned from amateur tournaments.

The “Open Era” of tennis began in 1968, a revolutionary step initiated by Britain’s Lawn Tennis Association (LTA), which voted to abolish the amateur-pro distinction despite threats from the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF). This forced the ILTF to approve open tournaments, allowing professionals and amateurs to compete for prize money. The first open tournament was the British Hard Courts at Bournemouth in April 1968, followed by the French Open in May. Prize money quickly escalated, with top players earning millions annually.

The establishment of the four Grand Slam tournaments was crucial for the sport’s global visibility and professional structure.

- Wimbledon: 1877

- US Open: 1881

- French Open: 1891 (major in 1925)

- Australian Open: 1905

These tournaments, designated “Official Championships” by 1923, offer the most ranking points, prize money, and media attention.

Legendary figures who significantly contributed to tennis’s global appeal include:

- Rod Laver

- Billie Jean King

- Björn Borg

- Chris Evert

- Martina Navratilova

- Steffi Graf

- Pete Sampras

- Roger Federer

- Rafael Nadal

- Novak Djokovic

- Serena Williams

Their dominance and rivalries have captivated millions worldwide.

The International Tennis Federation (ITF), founded in 1913, remains the governing body for world tennis . The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), established in 1972, and the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA), founded in 1973, govern the men’s and women’s professional circuits, respectively, collaborating with the ITF.

Modern Innovations and Future Trajectories

The evolution of tennis continues with significant modern innovations impacting various aspects of the game.

Technological Advancements:

- Hawk-Eye System: Since 2005, Hawk-Eye technology has revolutionized line calling, providing electronic review and a point-challenge system . Its “Hawk-Eye Live” implementation makes real-time line calls, enhancing accuracy . This system, which tracks ball trajectory with cameras, is also used in cricket, rugby, and football.

- Data Analytics and Sports Science: These have profoundly influenced training and match analysis. Sub-second skeletal tracking provides insights for officiating, broadcast, and team analytics in sports like basketball.

- Equipment Customization: Modern rackets are highly customizable, allowing players to tailor grip size, string tension, and balance to suit their playing styles, enhancing performance and preventing injuries.

- Apparel and Footwear: Apparel has shifted to high-performance synthetic fabrics that wick moisture and breathe, keeping players comfortable. Footwear incorporates advanced cushioning and support systems to distribute impact, reduce strain, and improve stability for quick movements.

Modern Training Methodologies: Modern Tennis Methodology (MTM), developed by Oscar Wegner, represents a significant shift in coaching. Wegner observed that traditional teaching methods differed from how top players actually played. His methodology emphasizes natural mechanics, timing, and tracking the ball in front, often contrasting with traditional advice like “racket back early” or “close your stance”. MTM promotes open stance, hitting up and across, lifting the body, and heavy topspin. This system, which makes tennis easier to learn, has been adopted by top tennis nations like Spain, Argentina, and Serbia, and was notably used by the Williams sisters.

Fan Engagement Strategies: With 106 million people playing tennis worldwide—a 25.6% increase in five years—and Britain leading in participation rates , connecting with this growing fanbase is crucial. Strategies include:

- Leveraging Social Media: Real-time updates, exclusive content, live Q&A sessions, and short-form videos.

- Engaging In-Stadium Experiences: Special performances, interactive fan cams, light displays, and digital integrations like mobile apps.

- Data and Personalization: Collecting fan data for personalized marketing and improved game-day experiences.

- Interactive Contests and Giveaways: Offering prizes like free tickets or signed memorabilia.

- Second-Screen Experiences: Live streaming with additional content like behind-the-scenes footage.

- Community Engagement: Special memberships, fan clubs, and in-person meetups.

- Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR): Leveraging immersive experiences.

- Fan Polling and Prediction: Engaging fans with polls on “all-time greats” or “match winners.”

The global tennis market is projected to reach USD 8.9 billion by 2032, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.14% from 2024 . This growth is driven by increasing accessibility, rising popularity among recreational players, the growth of the professional circuit, and continued technological advancements in equipment.

A Dynamic Legacy

The evolution of tennis is a compelling narrative of adaptation, innovation, and strategic integration of lessons from diverse sporting traditions. From its ancient hand-ball precursors and the intricate “jeu de paume” played in medieval monasteries, to the formalized “real tennis” of kings, and finally to the modern game, the sport has consistently absorbed and refined elements from its predecessors and contemporaries. The transition from bare hands to sophisticated composite rackets, the pragmatic adaptation of croquet lawns for court dimensions, and the enduring, albeit mysterious, scoring system all speak to a sport shaped by both deliberate design and organic development.

Its journey highlights how external technological advancements, such as the lawn mower, can profoundly enable transformation, and how pre-existing infrastructure can accelerate popularization. It also underscores the critical role of visionary innovators and strong governing bodies in standardizing rules, fostering international competition, and ensuring global growth. The game’s unique blend of tradition and continuous technological advancement, from Hawk-Eye line calls to advanced training methodologies, demonstrates its capacity for dynamic evolution.

Today, tennis stands as a global phenomenon, driven by professional tours, iconic Grand Slam tournaments, and a growing, engaged fanbase. Its rich history, deeply intertwined with the “lessons” learned from other sports and societal shifts, ensures continued relevance and appeal. As technology advances and fan engagement strategies become more sophisticated, the future of tennis promises even greater accessibility, competitive intensity, and global reach. Its enduring legacy is a testament to its remarkable ability to adapt, innovate, and captivate audiences across centuries and cultures.