The Man in the Lab Coat

The mid-20th century grappled with a haunting question: How do everyday individuals become complicit in horrific deeds? The unfathomable scale of the Holocaust, a genocide orchestrated by Nazi Germany during World War II, left the world reeling. Adding to the unease was the defense offered by figures like Adolf Eichmann, a central architect of the “Final Solution,” who notoriously claimed he was merely “following orders.” This profound moral quandary wasn’t just a historical footnote; it compelled social psychologist Stanley Milgram to seek answers. Instead of poring over historical records, Milgram chose a different path: a meticulously designed laboratory experiment at Yale University in 1961. His goal was to understand the extent to which people would defer to authority, even when asked to inflict suffering. Eichmann’s chilling rationale served as a powerful catalyst for Milgram’s groundbreaking investigation into the human tendency to obey.

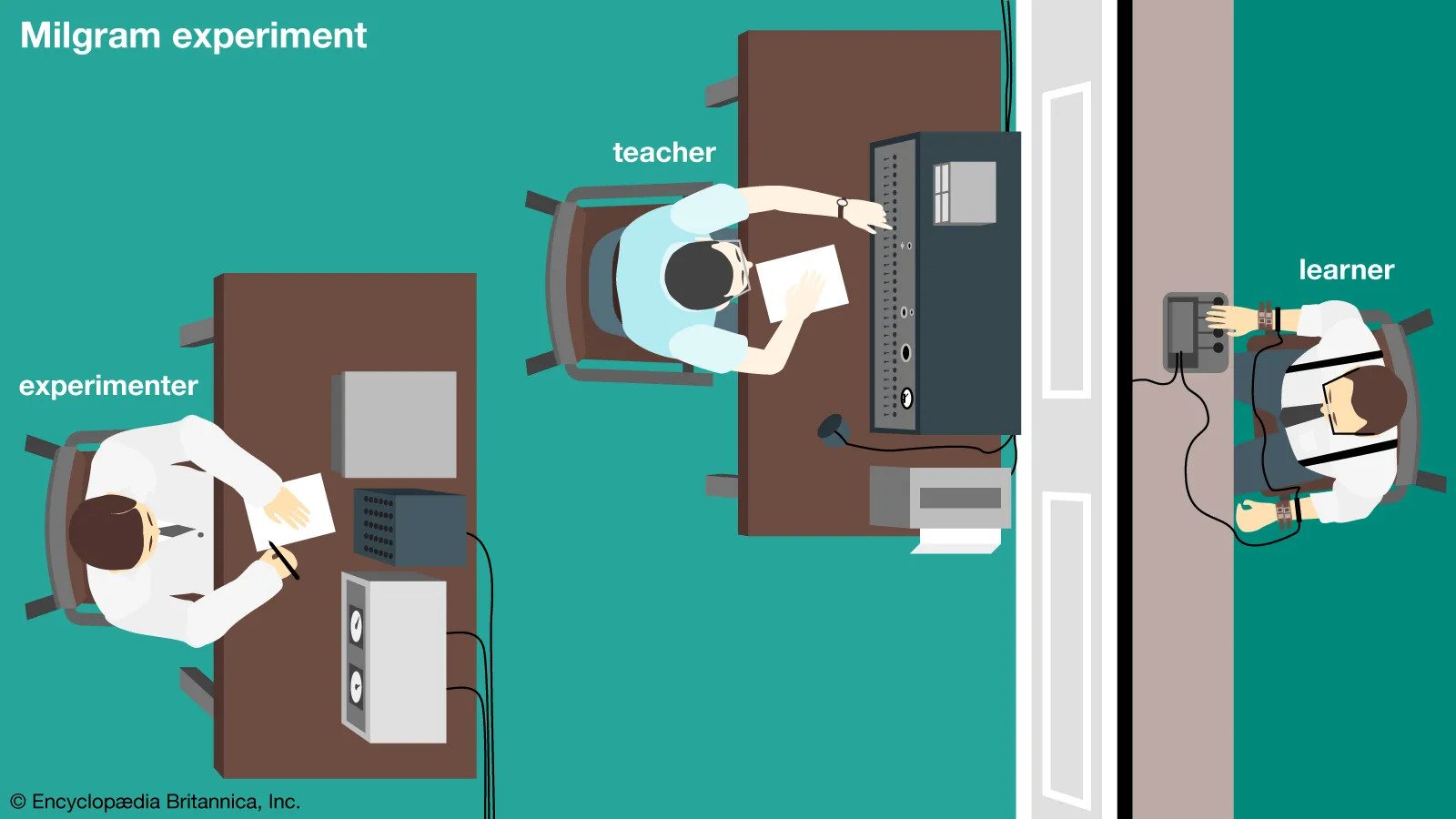

The idea was to create a situation where an ordinary person was ordered by a credible authority figure to inflict pain on a stranger. Milgram wanted to measure how far someone would go. To achieve this, he devised a simple but deceptive scenario with three distinct roles:

- The Experimenter: An actor in a gray lab coat, exuding an air of calm, professional authority. This figure directs the experiment.

- The Teacher: The only genuine participant in the study. This individual was recruited through a newspaper ad and believed the experiment was about memory and learning.

- The Learner: An actor and confederate of Milgram’s. His real name was James McDonough, but he was known in the experiment by the pseudonym “Mr. Wallace.” The Teacher believed the Learner was another volunteer.

Upon arrival, a rigged draw always assigned the true participant to the role of Teacher. The Teacher watched as the Learner was strapped into a chair and had electrodes attached to his wrist, all while the Learner mentioned a mild heart condition. The Teacher was then seated in an adjacent room in front of an imposing shock generator. Their task was to read word pairs to the Learner and, for every incorrect answer, deliver an electric shock, increasing the intensity by 15 V each time. The real question was: would the Teacher obey the Experimenter’s commands to continue, even as the Learner screamed in apparent agony?

The Experiment at a Glance

- Location & Date: Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, August 1961.

- Participants: 40 men aged 20-50 from diverse occupations (e.g., postal clerks, engineers, high school teachers). They were paid $4.50 (equivalent to over $45 in 2025) for their time, regardless of their actions.

- Roles:

- Teacher: The real subject being studied.

- Learner: A confederate (actor James McDonough, known as “Mr. Wallace”) pretending to be shocked.

- Experimenter: An authority figure in a lab coat giving the orders.

- Task: Administer a supposed 15 V shock for the first wrong answer, then increase the voltage by 15-volt increments for each subsequent mistake. The generator’s dial escalated from “Slight Shock” to “Danger: Severe Shock” and finally to “XXX” at 450 V.

- Objective: To measure how far an individual would proceed when an authority figure instructed them to perform actions that conflicted with their personal conscience.

The Standard Four “Prods”

When a Teacher hesitated, the Experimenter used a sequence of four calm, standardized commands to pressure them to continue:

- “Please continue.” or “Please go on.”

- “The experiment requires that you continue.”

- “It is absolutely essential that you continue.”

- “You have no other choice; you must go on.”

What the Learner Experienced

The Learner’s reactions were pre-scripted and played from a tape recorder. The table below shows the scripted response at each voltage level and the number of subjects in the original “Voice Feedback” variation who refused to continue at that point.

| Voltage (V) | Scripted Learner Reaction | # of Teachers Who Stopped |

|---|---|---|

| 75 | A small grunt | 0 |

| 120 | Shouts: “Ugh! Hey, this really hurts!” | 0 |

| 150 | “Ugh! Experimenter! That’s all. Get me out of here. I refuse to go on!” | 0 |

| 200 | Mentions heart trouble, screams intensify | 0 |

| 300 | Screams and refuses to provide more answers | 5 |

| 315 | Intense scream, then more pounding on wall | 4 |

| 330 | Agonized screams, then ominous silence | 2 |

| 345 | Silence | 1 |

| 360 | Silence | 1 |

| 375+ | Total silence | 1 |

| 450 (XXX) | (Remained Obedient) | 26 (65%) |

Results & Key Variations

Milgram conducted nearly two dozen variations of the experiment. The physical and emotional distance from the “Learner” was a key variable affecting obedience. While the 65% obedience rate (26 of 40 participants) in the primary experiment is the most cited figure, it is crucial to emphasize that 35% of participants successfully defied the authority figure and refused to deliver the final shocks.

| Condition | Obedience (% Delivering Full 450 V Shock) | Mean Max Voltage |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Remote Victim) | 65% | 405 V |

| Voice Feedback (Most Cited) | 62.5% | 367.5 V |

| Same Room (Victim Visible & Audible) | 40% | 312 V |

| Touch Proximity (Teacher Forces Hand) | 30% | 268.2 V |

Takeaway: Obedience dropped significantly as the Teacher’s proximity to the Learner’s “suffering” increased. However, the presence of the authority figure was enough to keep a substantial number of participants compliant even under the most direct conditions.

Technical & Methodological Critiques

| Issue | Critics & Evidence | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Demand Characteristics | Orne & Holland (1968) argued that participants knew the setup was fake and were merely playing a role they believed the scientists wanted. | Threatens the study’s internal validity. It may have measured trust in scientific authority, not pure obedience. |

| Archival Inconsistencies | In her book Behind the Shock Machine, psychologist Gina Perry analyzed archived recordings and found evidence of greater resistance and more procedural variations than Milgram reported in his official papers. | Suggests that compliance rates may be inflated and that the experimental procedure was not as standardized as claimed. |

| Sampling Limitations | The original studies used only male participants from the New Haven area who volunteered for a cash reward. | Findings are not easily generalizable across genders, cultures, or situations where obedience is not compensated. |

| Experimenter Bias | Researchers have noted that in some sessions, the Experimenter went off-script, issuing more than the standard four prods to coerce defiant participants. | The pressure applied was inconsistent, making it difficult to compare results across participants fairly. |

Ethical Storm: Then & Now

- Deception & Informed Consent: Participants were deceived about the purpose of the study and the reality of the shocks, a clear violation of today’s ethical codes (e.g., APA Code 8.07).

- Psychological Harm: Many participants exhibited extreme stress: sweating, trembling, stuttering, and even nervous laughter and seizures. Critic Diana Baumrind condemned the experiment for the “inflicted insight” and psychological distress it caused, which she argued was potentially traumatic.

- Right to Withdraw: While participants could technically leave, the Experimenter’s prods were designed to make this difficult, infringing on their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

- Debriefing: Milgram did conduct a debriefing session where he revealed the deception and reunited the Teacher with the unharmed Learner. However, follow-up questionnaires revealed that some participants left with lingering doubts and guilt.

- Legacy: The intense ethical backlash against Milgram’s work was a major catalyst for the development of modern ethical guidelines and the establishment of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) to protect human research subjects.

Replications & Modern Insights

Direct replication is now ethically impossible. However, modified replications continue to yield troubling results.

- Burger (2009): Jerry Burger replicated the experiment but stopped at the 150 V mark, the point at which the Learner first demands to be let out. He found that 70% of participants were willing to continue past this point, a rate not significantly different from Milgram’s.

- Dolinski et al. (2017) in Poland: A replication in a different cultural context found that 90% of participants were willing to go to the highest level in their modified setup.

- Virtual-Reality Version (2018): A study using a VR avatar as the Learner found that participants exhibited physiological stress responses and empathy but still complied with the authority’s instructions.

- The Trend: Despite decades of increased awareness, the fundamental tendency to obey a perceived legitimate authority figure, even when it conflicts with moral values, remains potent.

Why the Study Still Matters in 2025

The “shock box” may be a museum piece, but the dynamics it exposed are more relevant than ever.

- Algorithmic Authority: Ride-share drivers, gig workers, and warehouse employees are often managed by opaque algorithms that dictate their tasks and measure their performance. Research shows this “algorithmic management” can exert powerful control, echoing the disembodied authority of the Experimenter.

- Public Health & Crises: The COVID-19 pandemic provided a global case study in obedience, with governments issuing mandates on masking, lockdowns, and vaccinations. The varying levels of compliance and defiance highlighted the same tensions Milgram explored.

- Military & Policing: The study’s lessons are now integrated into training programs that focus on ethical decision-making and the duty to disobey unlawful or immoral orders.

- Corporate Culture: Whistleblower programs and ethics hotlines are modern organizational structures designed to counteract the diffusion of responsibility and blind obedience that can lead to corporate scandals.

- Disinformation & Social Media: Online influencers and anonymous accounts can become powerful, if illegitimate, authority figures, capable of swaying mass behavior and belief through the spread of misinformation.

Actionable Strategies to Counter Blind Obedience

- Foster Ethical Climates: Leaders must actively encourage employees and team members to question directives that conflict with stated values.

- Empower Dissent: Research shows that seeing a peer rebel dramatically increases defiance. In high-stakes environments, “buddy systems” or dissent-positive protocols can be effective.

- Demand Algorithmic Transparency: When authority is automated, workers and consumers should have a right to understand the rules and challenge unfair or harmful directives.

- Practice Ethical Resistance: Use simulations and role-playing (e.g., in VR) to allow people to practice resisting unjust authority in a safe environment.

- Protect Whistleblowers: Robust, anonymous, and legally protected channels for reporting wrongdoing are crucial for breaking the chain of harmful obedience.

The Echo of the Shock Box

Stanley Milgram’s experiment revealed a difficult truth: the capacity for ordinary people to follow orders, even to a harmful conclusion, is a deeply ingrained part of the human condition. The forces he studied—authority, distance, and responsibility—did not vanish after 1961. They now operate through new mediums, from corporate hierarchies and military chains of command to the algorithms on our phones. Understanding the mechanisms of blind obedience is the first step toward building a culture where critical thinking and moral courage can triumph over the simple, and sometimes dangerous, directive to “please continue.”