A Revelation in the Twilight of Idols

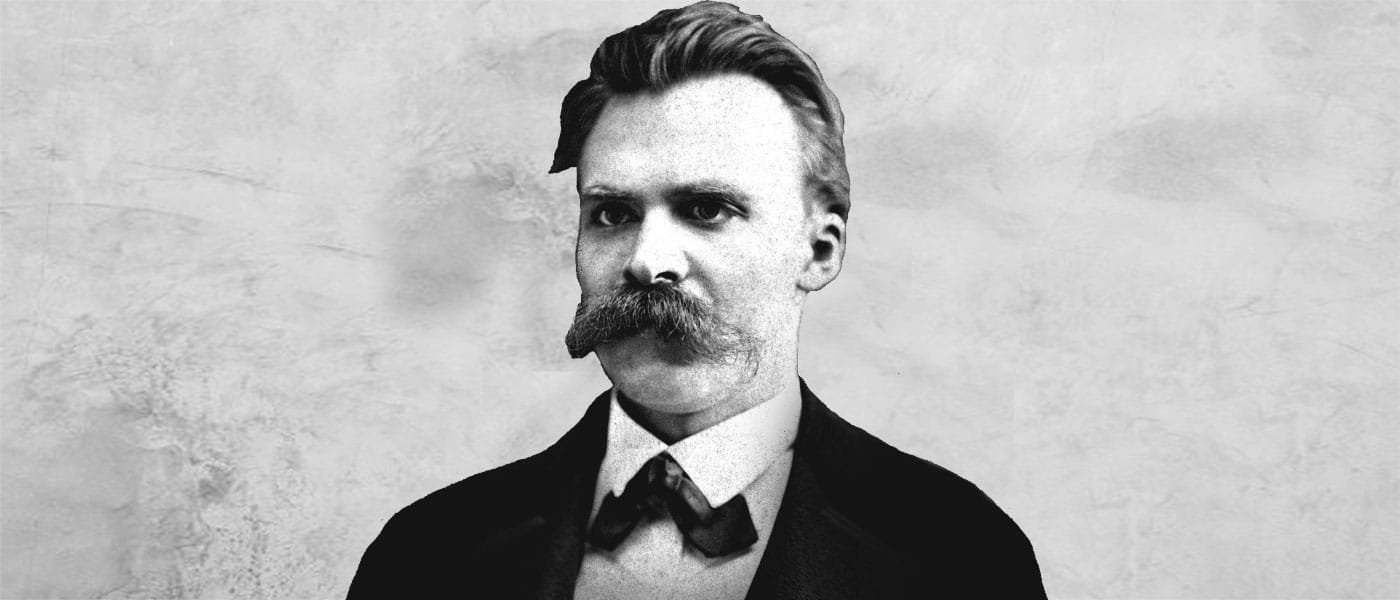

Friedrich Nietzsche, a philosopher known for his radical critiques, declared in Twilight of the Idols: “Dostoiewsky who, incidentally, was the only psychologist from whom I had anything to learn”. This profound statement from a thinker who sought to dismantle “old truths” highlights Dostoevsky’s unique importance. Nietzsche’s praise was a direct critique of the prevailing academic psychology of his time, like Wilhelm Wundt’s, which he found superficial. Nietzsche, who considered himself a “grand psychologist”, sought a deeper understanding of the human soul that ventured “beyond good and evil”. Dostoevsky’s unflinching exploration of humanity’s “irrational parts” provided this radical lens.

Nietzsche also noted that Dostoevsky “afforded the greatest relief to my mind”. This suggests a deep, personal resonance. Dostoevsky’s raw portrayal of madness, evil, and the “shadow self” may have validated Nietzsche’s own unsettling observations, opening a “window to the soul that had appeared jammed”. This intellectual kinship, exploring the “contradictory nature of the Self”, might have intensified Nietzsche’s own psychological journey.

Ultimately, Dostoevsky offered Nietzsche unparalleled insights into the human psyche’s irrational and profound depths. His characters embodied the very psychological phenomena Nietzsche sought to diagnose and transcend, challenging conventional psychology and morality.

Fyodor Dostoevsky: A Life Forged in the Crucible of Experience

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) began his literary career after studying military engineering. Unlike many contemporaries, he was not born into the gentry, a fact he often highlighted. His life was marked by traumatic events that profoundly shaped his understanding of the human condition. In 1849, he endured a mock execution, facing a firing squad before his sentence was commuted to hard labor in Siberia. This period, along with his struggles with epileptic seizures, provided him with unparalleled material for psychological analysis.

Dostoevsky specialized in analyzing “pathological states of mind that lead to insanity, murder, and suicide” and exploring “emotions of humiliation, self-destruction, tyrannical domination, and murderous rage”. His direct exposure to human extremity allowed him to portray characters with unmatched psychological depth. This authenticity, a “lived, rather than intellectual grasp of truth”, deeply appealed to Nietzsche, who valued direct experience over abstract idealism. Dostoevsky vividly depicted how “early trauma could lead to adaptive behaviours that were compulsive, reactive, and excessive”, foreshadowing modern psychological understandings of trauma.

The “Only Psychologist”: Unpacking Nietzsche’s Profound Admiration

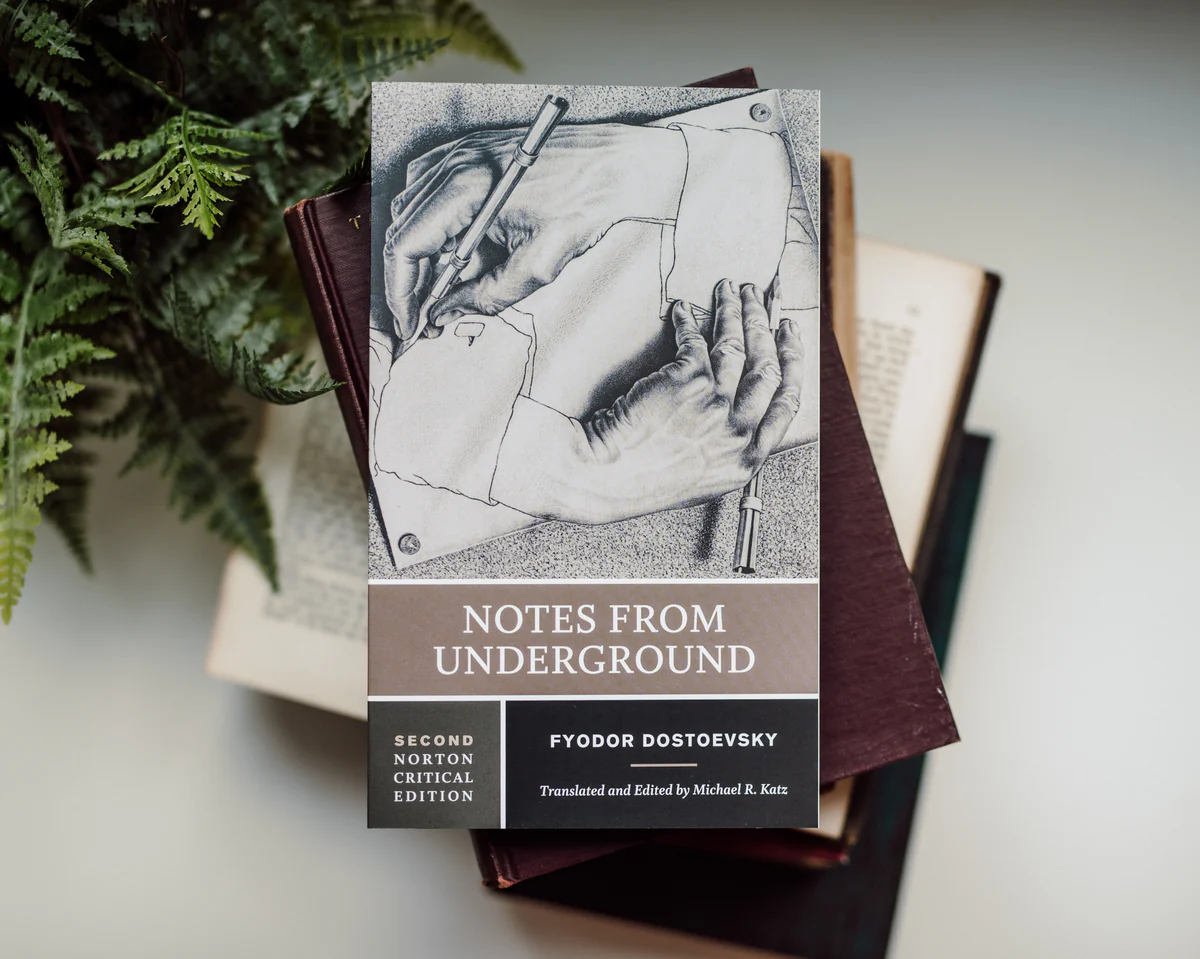

Nietzsche discovered Dostoevsky’s works relatively late, in 1887, primarily through

L’esprit souterrain, the French translation of Notes from the Underground. This encounter was a revelation.

Nietzsche’s high regard for Dostoevsky implicitly critiqued the superficial psychological frameworks of his era. While academic psychology focused on empirical study, Dostoevsky delved into “unconscious motivations, the complexities of selfhood, and the enduring influence of childhood trauma”. This resonated with Nietzsche’s vision of a psychology that dared to venture “beyond good and evil”.

A significant influence was the concept of ressentiment, which Nietzsche likely derived from Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground. The “Underground Man” exemplifies this state: a “man of ‘heightened consciousness’ who does not immediately strike back upon being hit, but plots and thinks and analyses his revenge instead”. This lingering resentment, born from weakness, informed Nietzsche’s “psychology of slave morality”.

Nietzsche’s statement that Dostoevsky “afforded the greatest relief to my mind” is telling. This relief came from Dostoevsky’s willingness to expose the “morbidity, evil and madness” within human nature, acknowledging that “we all have the potential to be criminal or saint”. This recognition of the “shadow” self could be paradoxically consoling. Dostoevsky’s unflinching depiction of internal struggles, even if leading to “despicable acts”, provided Nietzsche with “amoral” psychological observations, which he used as empirical data for his revaluation of values.

Dostoevsky’s Psychological Masterpieces: Case Studies of the Human Soul

Dostoevsky’s novels are profound psychological inquiries, presenting characters as intricate case studies of the human soul.

The Underground Man: A Precursor to Existential Angst

The narrator of Notes from the Underground is an “astonishing anti-hero”, a “sick man,” “spiteful,” and “unattractive”. He embodies an “overdeveloped moral consciousness, which paralyzes his capacity for action”, grappling with self-loathing and alienation. He argues that humans prioritize free will, even if irrational, over pure reason. His challenge to scientific determinism and utopian ideals aligns with Nietzsche’s critique of rationalism and emphasis on the will. The Underground Man’s “resentment” provided Nietzsche with crucial material for his concepts of ressentiment and slave morality.

Raskolnikov’s Torment: Crime, Guilt, and the Burden of Freedom

Raskolnikov, in Crime and Punishment, commits murder based on “utilitarian principles,” plunging him into “moral and psychological crises”. The novel is a “classic psychological study” of crime and punishment, exploring “alienation, poverty and nihilism”. Raskolnikov’s journey highlights the “duality of human nature” and the “dangers of ideological rigidity”. His internal conflict, nightmares, and hallucinations create intense psychological tension. The true punishment, the novel suggests, is profound “mental anguish”. While Dostoevsky shows Raskolnikov’s “redemptive arcs”, Nietzsche likely saw his eventual embrace of Christianity as a “tragedy not a redemption story”, a failure to transcend slave morality.

The Karamazov Brothers: Faith, Doubt, and the Abyss of Free Will

The Brothers Karamazov explores “conflict between religious faith and doubt”, “moral responsibility”, and “the burden of free will”. Characters like Ivan, Dmitri, and Alyosha embody distinct belief systems, with their “unresolved tensions manifest as psychological turmoil”. Ivan Karamazov’s “Grand Inquisitor” parable critiques religion, arguing humans prefer “security, comforts, and protections” over the “burden of free will”. This resonates with Nietzsche’s critique of Christian morality as a system for the weak. Ivan’s nervous breakdown is a consequence of doubt and overwhelming moral responsibility.

Dostoevsky’s characters, from the Underground Man to Raskolnikov and Ivan Karamazov, represent psychological archetypes grappling with fundamental existential questions: freedom, nihilism, morality, and truth. Nietzsche found in them a living demonstration of his own philosophical concerns, even if their ultimate conclusions differed. Both Dostoevsky and Nietzsche intensely grappled with free will, seeing it as a burdensome force, though their proposed resolutions diverged significantly.

Dostoevsky’s Enduring Psychological Wisdom: Quotes for the Modern Mind

Dostoevsky’s genius extends beyond his intricate plots and complex characters to his profound aphorisms, which distill complex psychological truths into memorable statements. These insights remain remarkably relevant, offering guidance on self-deception, suffering, free will, and the human condition. They continue to resonate with contemporary psychological thought and individual self-understanding.

| Quote | Source (Novel) | Core Psychological Insight | Contemporary Relevance/Application |

| “Above all, don’t lie to yourself. The man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point that he cannot distinguish the truth within him, or around him, and so loses all respect for himself and for others. And having no respect he ceases to love.” | The Brothers Karamazov | The profound self-deception that leads to a loss of internal and external truth, eroding self-respect and the capacity for genuine connection and love. | Crucial in an age of pervasive misinformation, self-help culture emphasizing authenticity, and mental health discussions around self-awareness and integrity. Relevant for understanding cognitive biases and the importance of self-honesty in personal growth. |

| “Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart. The really great men must, I think, have great sadness on earth.” | Crime and Punishment | The intrinsic link between heightened consciousness, empathy, and the experience of suffering. Intellectual and emotional depth often correlates with profound sadness. | Resonates with discussions on the mental health challenges faced by highly intelligent or sensitive individuals, the burden of awareness, and the acceptance of suffering as part of the human condition. |

| “Man only likes to count his troubles; he doesn’t calculate his happiness.” | Notes from Underground | A fundamental human tendency towards negativity bias and ingratitude, overlooking blessings while fixating on misfortunes. | Applicable to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) principles, mindfulness practices, and gratitude exercises aimed at shifting perspective and improving well-being. |

| “The mystery of human existence lies not in just staying alive, but in finding something to live for.” | The Brothers Karamazov | The existential quest for meaning and purpose as the core driver of human life, beyond mere survival. | Central to existential therapy , Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, and modern discussions on purpose-driven living, mental resilience, and combating nihilism. |

| “Talking nonsense is man’s only privilege that distinguishes him from all other organisms. It’s by talking nonsense that one gets to the truth! I talk nonsense, therefore I’m human.” | Notes from Underground | The irrational, illogical, and seemingly absurd aspects of human thought and communication are not flaws but essential to our humanity and even pathways to deeper truths. | Challenges rigid rationalism, highlights the value of creative thinking, intuition, and even humor in understanding complex realities. Relevant to psychoanalytic concepts of the unconscious and the role of irrationality in human behavior. |

| “If there is no God, then everything is permitted.” | Demons (The Possessed) (paraphrased) | Explores the psychological and moral vacuum created by the absence of a transcendent moral authority, leading to radical freedom and potential nihilism. | A cornerstone of existentialist thought, discussions on secular ethics, the challenges of moral relativism, and the search for meaning in a post-religious world. Directly connects to Nietzsche’s “death of God” concept. |

| “To be in love is not the same as loving. You can be in love with a woman and still hate her.” | (General Dostoevsky insight) | Distinguishes between fleeting, passionate emotional states (“being in love”) and a deeper, more enduring, often difficult commitment or attitude (“loving”), which can coexist with negative feelings. | Useful for understanding complex relationship dynamics, the difference between infatuation and mature love, and the psychological complexities of attachment and ambivalence in human relationships. |

| “I love mankind, but I am amazed at myself: the more I love mankind in general, the less I love people in particular.” | Notes from Underground | The hypocrisy or psychological dissonance between abstract, idealistic love for humanity and the often-difficult, frustrating reality of engaging with individual human beings. | Highlights the challenges of empathy in action versus performative compassion, relevant to social activism, charity work, and the psychological toll of interpersonal relationships. |

| “I swear, gentlemen, that to be too conscious is an illness — a real thoroughgoing illness.” | Notes from Underground | Excessive self-awareness and intellectual rumination can lead to paralysis, indecision, and profound psychological suffering, hindering action and genuine engagement with life. | Directly relevant to modern discussions on overthinking, analysis paralysis, anxiety disorders, and the downsides of hyper-introspection in the digital age. |

| “The soul is healed by being with children.” | (General Dostoevsky insight) | The restorative power of innocence, simplicity, and unconditional connection found in interaction with children, offering a respite from adult complexities and suffering. | Speaks to the psychological benefits of nurturing relationships, the importance of play, and the often-overlooked therapeutic value of intergenerational connection, contrasting with the intellectual torment of his other characters. |

| “Human nature is not taken into account, it is excluded, it’s not supposed to exist! They don’t recognise that humanity, developing by a historical living process, will become at last a normal society, but they believe that a social system that has come out of some mathematical brain is going to organise all humanity at once and make it just and sinless in an instant, quicker than any living process!” | Notes from Underground (or related writings) | A critique of utopian rationalism and deterministic views of human nature, arguing that human beings are inherently unpredictable, irrational, and resistant to being wholly contained by logical systems. The “living soul demands life” and resists mechanical rules. | Highly relevant to critiques of technocratic solutions to social problems, the limitations of AI in understanding human complexity, and the enduring debate between free will and determinism in psychology and philosophy. |

Beyond the Obvious: Lesser-Known Facets of Their Connection

The profound connection between Nietzsche and Dostoevsky extends beyond their shared philosophical concerns into more subtle, yet equally significant, areas.

The Impact of French Translation (L’esprit souterrain)

Nietzsche primarily read Dostoevsky in French translations, particularly L’esprit souterrain. This translation was “pivotal” in shaping Nietzsche’s interpretation. It transformed the “Underground Man” from a philosophical-ideological critique of Russian nihilism into a “purely psychological type” for Nietzsche. This allowed Nietzsche to focus on the character’s psychological mechanisms of resentment and self-contradiction, integrating Dostoevsky’s raw psychological observations into his “beyond good and evil” framework , unconstrained by Dostoevsky’s original context or Christian solutions.

Nietzsche’s Appreciation for “Unbroken Natures” of Criminals

Nietzsche admired Dostoevsky as a psychologist partly because Dostoevsky “spent time among criminals” in prison and found them “the best, hardest, and most valuable material”. Nietzsche saw these criminals as “unbroken natures” who “cleaves to his fate and does not slander his deed after it is done”, contrasting with the “broken” natures of slave morality. This aligned with Nietzsche’s desire for a psychology that ventured “beyond good and evil,” appreciating strength even in transgressive acts. Nietzsche’s statement, “I am grateful to him in a remarkable way, however much he goes against my deepest instincts”, indicates his selective engagement: he sought psychological material that validated his own radical critiques of morality and human nature.

Shared Diagnosis of Nihilism, Divergent Solutions

Both Nietzsche and Dostoevsky were “great psychologists” who “understood and diagnosed the phenomenon of nihilism probably better than any other intellectuals of the nineteenth century”. They both argued against “modern rationalism and nihilism”. However, their solutions differed fundamentally. Nietzsche believed nihilism was the “direct result of Christianity”, leading to the “death of God” and necessitating “new set of morals”. Dostoevsky, conversely, saw nihilism as the “result of society forgetting God”, with his works often leading characters toward “Christian understanding of salvation”. While Dostoevsky viewed the “Overman” concept as leading to “enslavement and destruction”, Nietzsche considered Christian love a form of “slave morality”. Their intellectual paths converged in diagnosing nihilism but diverged sharply in their proposed remedies.

A Legacy of Profound Self-Scrutiny

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s contribution to understanding the human psyche is unparalleled. His intuitive grasp of internal conflict, irrational depths, human duality, and the profound consequences of free will resonated deeply with Friedrich Nietzsche’s radical philosophical project. Dostoevsky’s “literary psychologism” offered a depth of character analysis that transcended the academic psychology of his era, providing Nietzsche with invaluable material for his explorations of morality, power, and the human condition.

Dostoevsky’s insights remain remarkably relevant today. His exploration of “unconscious motivations, selfhood, and the influence of childhood trauma” foreshadowed psychoanalysis, while his grappling with meaninglessness, free will, and authenticity laid groundwork for existential philosophy. His works are often described as “prophetic” due to their accurate predictions of revolutionary behavior and timeless insights into human nature.

Dostoevsky’s novels remain a “window into the irrational parts of humanity that we often try to brush away”, forcing readers to confront uncomfortable truths. To engage with his works is to embark on a transformative journey into the depths of the human soul—a journey that is often harrowing, yet ultimately consoling in its profound recognition of shared human experience. For those seeking to understand the intricate workings of the mind, the enduring mysteries of human choice, and the timeless struggle for meaning, delving into Dostoevsky’s masterpieces offers an unparalleled opportunity for profound self-scrutiny and intellectual growth.