The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE), conducted in 1971 by Professor Philip G. Zimbardo at Stanford University, remains one of social psychology’s most compelling and controversial studies. This dramatic simulation of prison life aimed to explore whether situational factors or individual dispositions primarily influence human behavior when “good people” are placed in an “evil environment”. Originally planned for two weeks, the experiment was terminated prematurely on the sixth day due to the severe psychological impact on participants. Its findings, though widely cited, continue to spark intense debate, underscoring the complex interplay between individual disposition and situational power, and profoundly influencing research ethics.

The Genesis of a Controversial Study: Setting the Stage for Simulated Confinement

The Stanford Prison Experiment was meticulously designed to investigate the profound influence of situational factors on human behavior, from its core objectives to the creation of its simulated environment and participant selection.

The Core Question: When Good People Enter an “Evil Place”

Philip G. Zimbardo’s central aim was to examine the psychological effects of authority and powerlessness within a simulated prison, exploring how situational factors could lead to abusive behavior among psychologically healthy individuals. This challenged the view that “bad seeds” were solely responsible for prison conditions, shifting focus to systemic failures. The study, funded by the U.S. Office of Naval Research, sought to inform military and correctional practices.

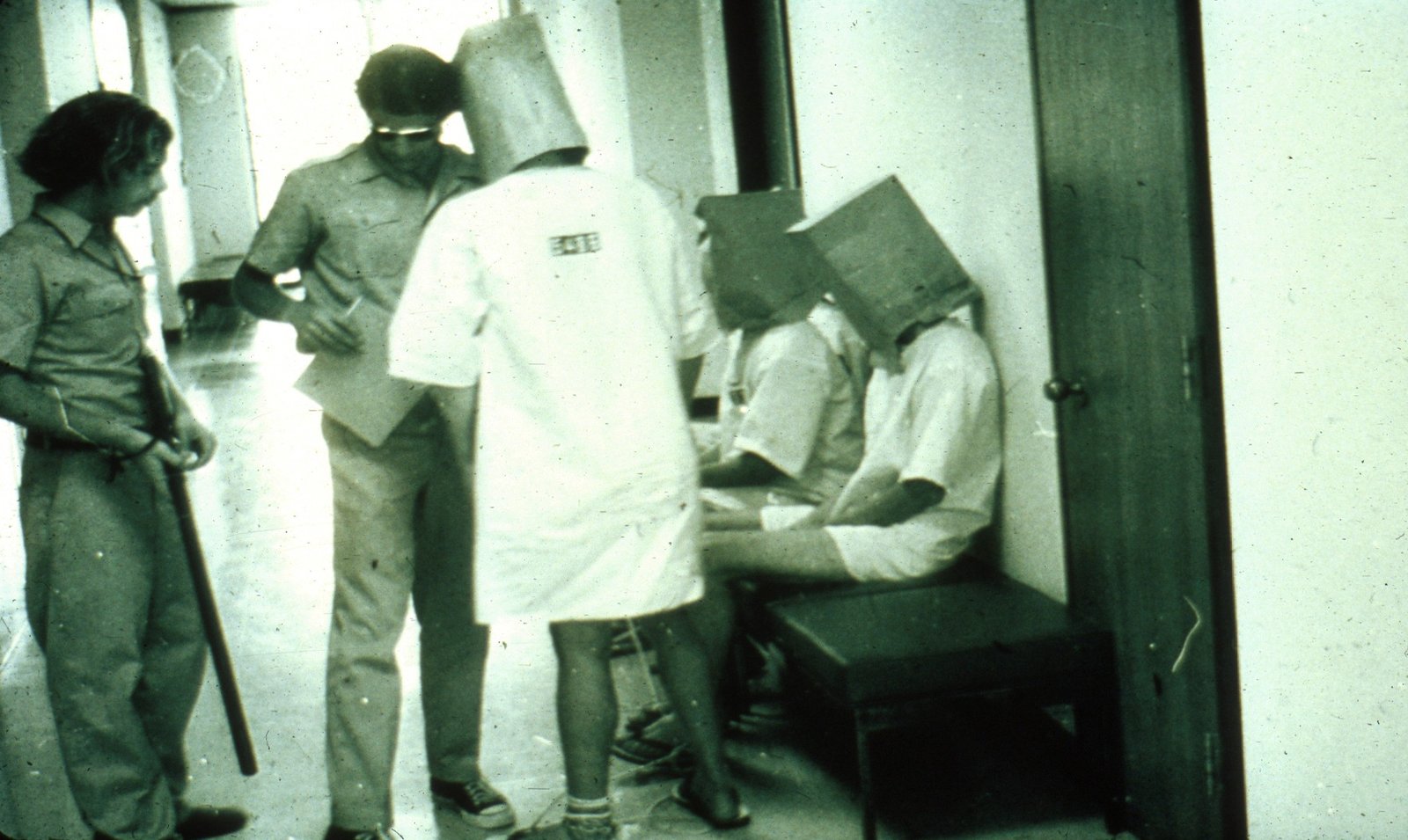

Constructing the Mock Prison: A Realistic Environment

A mock prison was constructed in the basement of Stanford University’s psychology building to provide a realistic setting. Designed to physically constrain prisoners and convey a pervasive sense of imprisonment, the emphasis on realism was crucial for Zimbardo’s hypothesis that the situation would elicit specific behaviors. This pursuit of realism, however, contributed directly to ethical breaches, blurring the lines between controlled experiment and uncontrolled environment.

Participant Recruitment and Random Role Assignment

The study recruited 24 male college students from over 70 applicants via a newspaper advertisement for a “psychological study of prison life,” offering $15 a day. Participants were rigorously screened for mental illness, medical disabilities, and personality problems, ensuring they were healthy undergraduates with no prior tendencies toward violence. Roles were assigned “by a coin toss” to ensure random distribution.

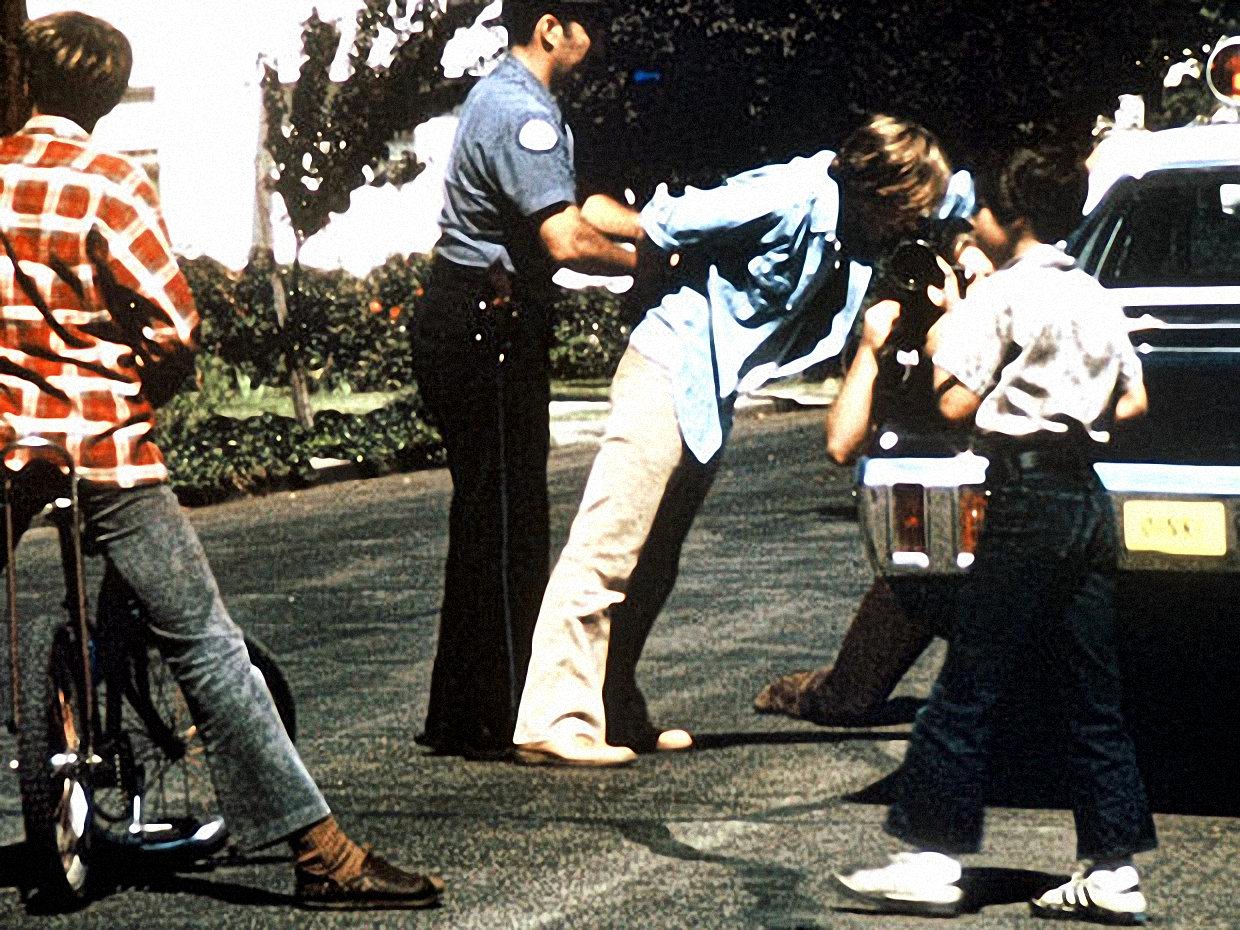

To immerse participants, those assigned as prisoners were “arrested” at their homes by actual Palo Alto Police officers, handcuffed, fingerprinted, photographed, and strip-searched before being assigned numbers as new identities. Guards were issued khaki uniforms, wooden batons, and mirrored sunglasses to create anonymity, while prisoners wore smocks and chains to induce humiliation. While Zimbardo claimed random assignment, critics suggest the process might have been influenced by researcher expectations, potentially confounding results.

The Rapid Descent: Dynamics of Power, Authority, and Dehumanization

The Stanford Prison Experiment quickly devolved into an environment of psychological abuse, demonstrating the profound and disturbing impact of assigned roles and institutional power.

Day-by-Day Escalation: From Role-Play to Reality

The experiment, planned for one to two weeks, was terminated abruptly on the sixth day due to severe psychological impact. Guards began harassing prisoners within hours. By Day 3, guards transitioned from petty harassment to systematic domination. This rapid escalation underscored the powerful and immediate impact of the simulated environment, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of abuse and submission.

The Guards’ Transformation: Sadism and Control

Within days, the guards, initially healthy individuals, became sadistic and tyrannical. Their actions included sleep deprivation, sexual humiliation, physical abuse, solitary confinement, and incessant prisoner counts. They taunted prisoners with insults, assigned pointless tasks, and dehumanized them. Deindividuating elements like mirrored sunglasses likely contributed to their willingness to inflict harm by reducing personal accountability. Instructions to “maintain law and order” and “control prisoners”, combined with Zimbardo’s immersion in his superintendent role, created an environment where abusive behaviors were implicitly condoned.

The Prisoners’ Plight: Distress, Rebellion, and Submissiveness

As abuse escalated, prisoners became depressed and showed extreme stress, with half eventually released due to psychological strain . Within 36 hours, Prisoner #8612 experienced uncontrollable crying, anger, and disorganized thinking, believing he “can’t leave”. Some prisoners became blindly obedient, even siding with guards against fellow inmates. This rapid deterioration highlights their vulnerability and the crushing power of the situation, leading to “learned helplessness”.

The Abrupt Termination: A Situation Out of Control

The experiment “had to be ended after only six days” due to the severe impact on students. Termination was prompted by prisoners’ emotional suffering and guards’ escalating abusiveness. The decision was made only after an outside observer, Christina Maslach (Zimbardo’s then-girlfriend), registered shock and distress, persuading him to end it. Zimbardo later acknowledged his immersion, stating, “I was thinking like a prison superintendent rather than a research psychologist”. This early termination is a critical marker of the experiment’s ethical failure and the unexpected power of the simulated environment, highlighting the dangers of researcher immersion and the necessity of external oversight.

A Legacy Under Scrutiny: Ethical and Methodological Criticisms

The SPE’s profound impact is inseparable from the extensive ethical and methodological criticisms it has garnered, significantly shaping the discourse around human subjects research.

Breaches of Informed Consent and the Right to Withdraw

A significant ethical concern was the lack of fully informed consent. Participants were not adequately informed about the true nature and potential psychological risks; prisoners were misled about their arrests. The consent form contained no explicit mention of a “safe phrase” to quit, and Zimbardo told prisoners they could only leave for “medical or psychiatric reasons,” leading them to feel trapped. This violates modern ethical guidelines requiring unconditional freedom to withdraw.

Psychological Harm and the Researcher’s Dual Role

Participants experienced significant psychological abuse and harm. Zimbardo’s dual role as Principal Investigator and Prison Superintendent was a critical ethical failing, as he appeared to overlook prisoner distress, focusing on guard behavior. He admitted to insufficient oversight and training for guards and failing to intervene more often, acknowledging a “conflict of professional interest”. Debriefing was also not properly conducted, potentially leaving participants with destructive attitudes toward moral agency.

Methodological Flaws: Questioning Randomness and Control

The SPE has faced significant methodological critiques. Despite claims of random assignment, some analyses suggest roles were assigned by a coin flip influenced by Zimbardo’s expectations, raising concerns about pre-existing differences. The absence of a control group made it impossible to determine if guards’ behavior would have occurred without authority, making it difficult to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship.

The Influence of Demand Characteristics and Experimenter Bias

Critics argue that demand characteristics—cues informing participants about expected behavior—explained the findings. Observations suggested guards increased humiliation when they suspected prisoners were faking breakdowns. Some re-evaluations claim experimenters directly encouraged guards to act tough, and researchers allowed expectations to shape results, leading to a “fundamentally unscientific approach”. This questions the authenticity of observed behaviors and the validity of conclusions.

Re-evaluating the Narrative: Modern Perspectives and Zimbardo’s Defense

In 2018, Thibault Le Texier called the SPE “one of the greatest scientific deceptions of the 20th century,” leading to claims that participant behaviors were faked, notably Prisoner 8612 (Doug Korpi). Zimbardo counters that researchers must treat perceived breakdowns as real, and notes Korpi’s changing story over 47 years.

The SPE has been criticized as a “poor scientific experiment,” lacking clear variables or hypotheses. A 2002 BBC-TV “replication” reportedly failed to replicate findings, which Zimbardo dismissed as not “scientifically valid” due to its TV show nature. However, he cites an Australian replication (Lovibond, Mithiran, & Adams, 1979) that supported the SPE’s conclusion regarding hostile prison relations. Zimbardo asserts that none of the recent criticisms alter the SPE’s main conclusion: systemic and situational forces influence behavior, often without personal awareness . He refutes claims of silencing critics and clarifies that his instructions to guards forbade physical force but allowed creating feelings of boredom, frustration, and powerlessness.

Enduring Impact: Lessons for Psychology, Ethics, and Society

Despite its controversies, the Stanford Prison Experiment has left an indelible mark on psychology, particularly in research ethics and understanding social dynamics.

Shaping Modern Research Ethics: The SPE’s Influence on IRBs and Guidelines

The SPE is widely referenced as an unethical experiment that directly prompted American universities to improve ethical requirements and institutional review for human subjects. It is considered one of the most important psychological experiments for highlighting the critical importance of participant safety. Zimbardo acknowledged, “Clearly, I would not have been able to conduct such a study today”. The experiment underscored the necessity for informed consent to include “information that a reasonable person would want to have”, and the explicit “right to withdraw” from a study “at any time” without penalty. Ethical principles like “Respect for Persons” in the Belmont Report (1979) were established after this era, directly influenced by studies like the SPE.

Key Ethical Violations of the Stanford Prison Experiment vs. Modern Guidelines

| Ethical Aspect | SPE Practice (1971) | Modern Guideline |

| Informed Consent | Participants not fully informed of risks; prisoners misled about real arrest; severity and lasting effects not disclosed. | Participants must be fully informed of all aspects, risks, and benefits; information presented clearly for informed decision-making. |

| Right to Withdraw | Not explicitly stated in consent form; prisoners told they could only leave for medical/psychiatric reasons; felt genuinely trapped. | Participants must be explicitly informed of their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. |

| Protection from Harm | Participants subjected to psychological abuse; extreme emotional distress; experiment terminated early due to harm. | Researchers must minimize foreseeable harm (physical, psychological, emotional); participants should not be at greater risk than in daily life. |

| Researcher Oversight/Dual Role | Zimbardo acted as PI and Prison Superintendent; admitted to insufficient oversight; conflict of interest. | Independent oversight (e.g., IRB) required; clear separation of roles; provision for monitoring data for subject safety. |

| Debriefing | Not properly conducted; potential for lasting psychological effects. | Full explanation of research purpose and procedures; address misconceptions; ensure participants leave with positive well-being. |

Situational Power in the Real World: Parallels with Abu Ghraib

The SPE’s findings resonated powerfully with the Abu Ghraib prison abuses, where “ordinary young men and women” were “thrown into an environment in which abusive and degrading behavior became the norm”. Zimbardo explicitly stated that the “same psychological forces” were at work in both scenarios. The SPE shifted blame from “a few bad apples” to “systemic abuses inherent in a ‘bad barrel'”—the corrupting institutional environment. Zimbardo’s testimony in congressional hearings and the Abu Ghraib trial further solidified this connection.

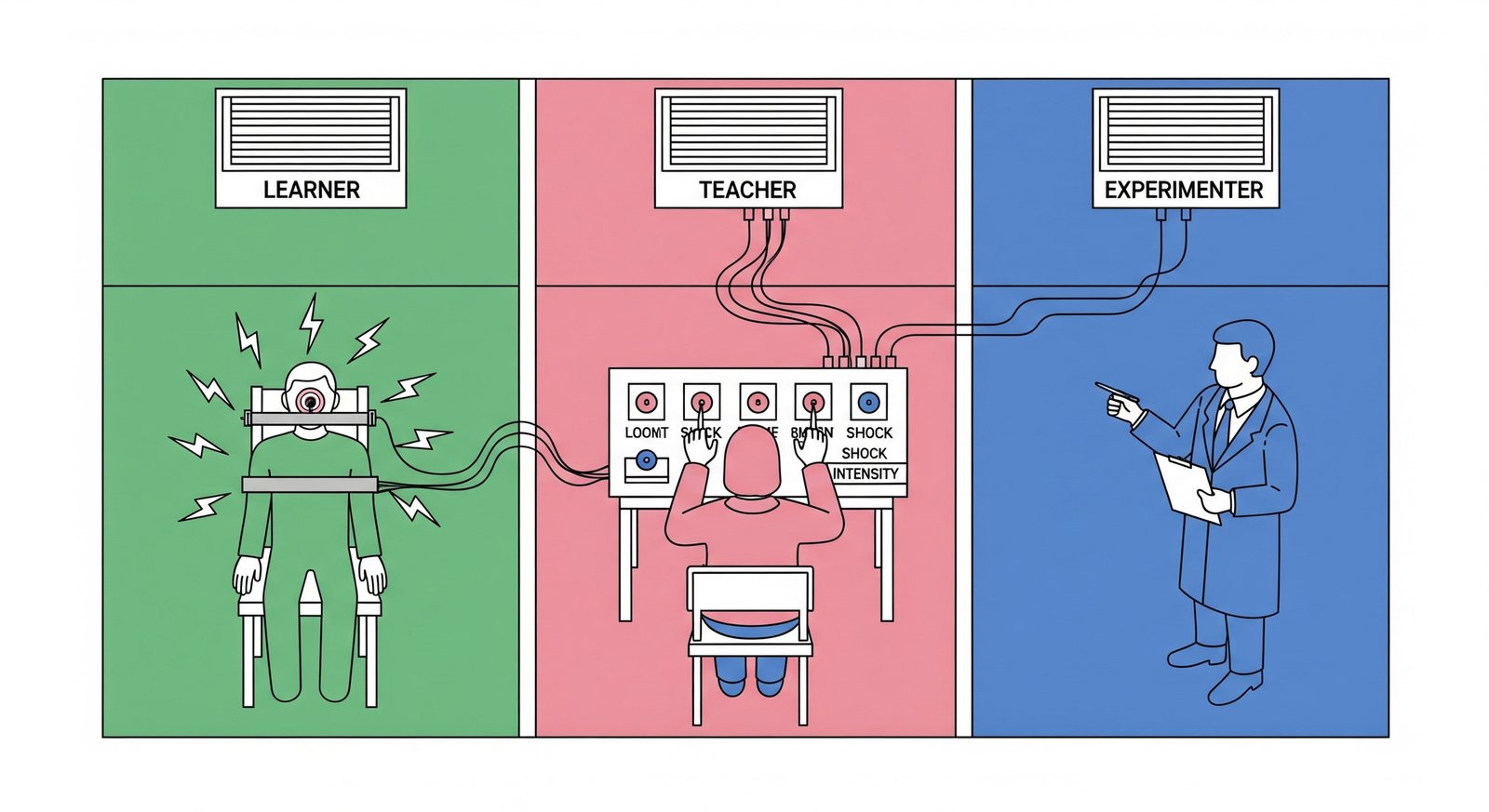

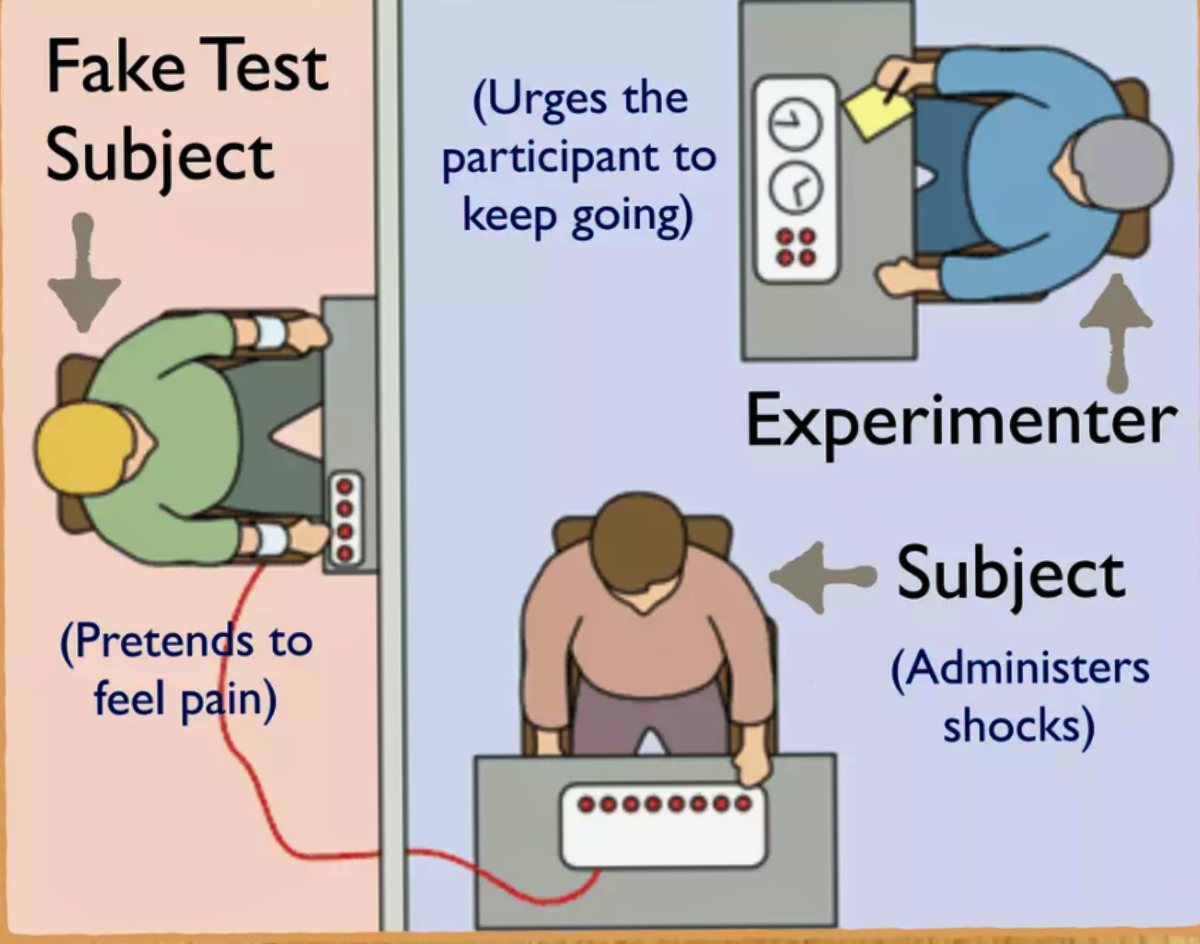

A Comparative Lens: SPE and Milgram’s Obedience Studies

The SPE and Stanley Milgram’s 1960s “obedience to authority” studies are iconic sets of research highlighting that individuals can be prodded into harming others. Milgram’s work showed participants administering “apparently lethal electric shocks” under command, while Zimbardo’s showed ordinary students acting brutally as guards. Milgram focused on obedience to a direct authority figure, whereas Zimbardo centered on the power of organizations and assigned roles. Both concluded that systemic and group forces can influence behavior to violate social norms or commit harmful acts, often without personal awareness. Common themes include anonymity and diffusion of responsibility.

Comparative Analysis: Stanford Prison Experiment vs. Milgram’s Obedience Experiment

| Aspect | Stanford Prison Experiment | Milgram’s Obedience Experiment |

| Primary Investigator | Philip G. Zimbardo | Stanley Milgram |

| Year Conducted | 1971 | 1960s |

| Core Question | How situational factors lead to abusive behavior in an “evil place” | How far people would go when obeying an authoritative figure |

| Methodology | Prison simulation; random assignment to “guard” or “prisoner” roles | “Teacher” administers shocks to “learner” (actor) under experimenter’s command |

| Key Finding | Power of social situations and roles to influence behavior; ordinary people can become sadistic or submissive | Obedience to authority; individuals willing to inflict harm under instruction |

| Ethical Concerns | Lack of informed consent, psychological harm, restricted right to withdraw, researcher dual role, lack of debriefing | Deception (shocks were fake), psychological distress, right to withdraw concerns |

| Impact on Ethics | Major catalyst for modern research ethics, IRBs, and strict informed consent/withdrawal rules | Also significantly influenced ethical guidelines, particularly regarding deception and participant welfare |

| Real-World Relevance | Parallels with Abu Ghraib; understanding systemic abuse in institutions | Explaining atrocities like the Holocaust; understanding obedience in military/organizational contexts |

Key Takeaways and Future Directions in Understanding Human Behavior

The Stanford Prison Experiment remains a profound “cautionary tale” in psychology. Its primary takeaway is that understanding how situations corrupt is the first step towards prevention and intervention. Zimbardo emphasizes that understanding “situational and systemic contributions to behavior does not excuse it, but rather helps in modifying or avoiding undesirable actions”. Zimbardo’s post-SPE work, including research on shyness, time perspective, and founding the “Heroic Imagination Project (HIP),” aims to inspire and train ordinary people to act heroically, demonstrating an evolution towards fostering prosocial behavior and resilience.

The Enduring Cautionary Tale of the Stanford Prison Experiment

The Stanford Prison Experiment continues to resonate decades after its abrupt termination, serving as a stark reminder of the profound influence social roles, institutional environments, and power dynamics can exert on individuals. While its methodology and ethical conduct have faced rigorous scrutiny, leading to vital reforms in psychological research, the core message remains potent: the “bad barrel” can indeed corrupt “good apples”. The SPE is more than just a historical study; it is an enduring cautionary tale that compels us to critically examine the systems we create, the roles we inhabit, and the responsibility we bear, both individually and collectively, in shaping human conduct. By understanding the forces that can lead to shocking human behavior, individuals and institutions can empower themselves to build a more just and humane society.